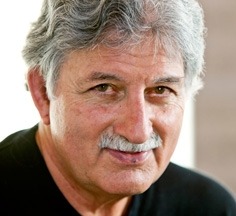

Edward Mazria thought he knew the impact of his field on the environment. An award-winning architect, he had a 40-year record of innovation and advocacy in sustainable building. He had long been aware of the dangers of global warming, and energy efficiency had always been a component of his designs.

But Mazria was surprised when in 2002 his analysis of U.S. Energy Information Administration data revealed the true impact of construction on the environment. The building sector, he concluded from the data, consumes approximately half of all energy production and is responsible for about half of all greenhouse gas emissions.

“The focus had been on the transportation sector, worrying about SUVs,” Mazria says. “But all the autos, SUVs, minivans and light-duty trucks were responsible for 16.6 percent of all U.S. energy consumption.”

In 2003, Mazria decided to do something about it. As part of his practice in Santa Fe, he started and financed a research organization, Architecture 2030, to facilitate dramatic reductions in energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. In 2006 he left his lucrative practice, incorporated Architecture 2030 as a nonprofit organization and issued the 2030 Challenge, a set of benchmarks for reducing energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in the built environment (buildings, homes and other man-made structures) to “net zero” by 2030.

“I realized that we have the solutions, but nobody had put them all together,” Mazria says.

Ripples of excitement spread through the building community. The challenge was immediately adopted by the 80,000-member American Institute of Architects and, a few months later, a resolution was passed at the U.S. Conference of Mayors calling for the adoption of the challenge by all cities. This year Architecture 2030 introduced a related initiative, the 2030 Challenge for Products, to set benchmarks for reducing the carbon footprint of the manufacturers who supply the building industry. Mazria will donate his Purpose Prize award to further the work of the nonprofit Architecture 2030.

Thank basketball

None of this would have happened had Mazria, now 70, not been spotted playing basketball in a high-profile pickup game in his native Brooklyn, N.Y., shortly after high school graduation. A coach from the Pratt Institute saw him and offered him a full four-year scholarship to join the Brooklyn-based college’s team.

“No one in my family had attended college,” he says, “and I expected to go to work with my father, who was a dry goods merchant.”

But the 6-foot-6-inch teenager had a real talent and love for the game, and the offer appealed to him. “I didn’t even know what Pratt was,” he admits. “The coach told me about the different courses of study – culinary arts, graphic design, engineering and architecture. Architecture sounded interesting, so I said, ‘Okay, I’ll take that.’”

Upon graduation from Pratt, Mazria did a stint in the Peace Corps in Arequipa, Peru, and spent a summer as a draftee at the training camp of the New York Knicks. But he left basketball behind to embark on his career in earnest, first as an architect with Manhattan’s Edward Larrabee Barnes Associates, later teaching architecture at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

Getting to know solar

Concern for the environment was growing in the wake of the energy crisis of 1973, and the University of Oregon in Eugene invited him to teach several courses, including one on solar energy. Not knowing anything about the topic, Mazria remained in sunny Albuquerque to study up on it. The few books available on the subject were dense, indecipherable tomes written by engineers.

He enlisted the aid of an engineer friend to “translate” the books into plain English, then used the information to design a solar house. “By the time I got to Oregon, I was an expert on the subject,” says Mazria with a laugh.

Soon after, in 1979, he published his own volume, The Passive Solar Energy Book: A Complete Guide to Passive Solar Home, Greenhouse and Building Design, in plain, accessible language. The book is still considered by many to be the definitive text on the subject. (A structure with “passive solar” design collects, stores and distributes energy by nonmechanical means to provide heating in winter and cooling in summer, and to maximize natural light.) Mazria then joined with a group of passive-solar experts and traveled around the country giving training seminars to thousands of engineers and architects.

In the late 1970s Mazria returned to New Mexico. By the mid-1980s energy prices were down, and there seemed to be little interest in the topic of sustainability. Yet for the next three decades Mazria continued designing energy-efficient buildings, creating a successful practice that eventually employed 15 architects.

Big recognition

In 2003, a year after his groundbreaking research into the environmental damage caused by the building sector, Mazria got the word out through Metropolis, an architecture and design magazine. He approached editor-in-chief Susan Szenasy with his findings, and she agreed to publish a cover story on the role of the built environment in exacerbating climate change.

“Finally, someone was putting numbers on a daunting problem and pinpointing the responsibility,” recalls Szenasy. “Now we could connect climate change to architecture and the built environment, to a profession that is predisposed to do the right thing.”

And it has. In addition to the American Institute of Architects, adopters of the 2030 Challenge include such professional organizations as the U.S. Green Building Council; National Governors Association; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers; and the Union Internationale des Architectes, among many others, as well as 41 percent of U.S. architecture firms.

Congress also took notice. The 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act required all new federal buildings to meet the energy performance standards set forth in the 2030 Challenge starting in 2010. The city of Seattle has created the Seattle 2030 District, an interdisciplinary public-private collaborative working to create a high-performance building district downtown to meet the 2030 Challenge targets districtwide.

“There’s a real transformation happening in our approach to the built environment,” Mazria says. “The question is, can it happen fast enough?”

A voice of inspiration

While Mazria’s success as an advocate is attributable in part to his rigorous research and his skills as a speaker and teacher, it’s also a result of his ability to inspire others – particularly up-and-comers in the field – by offering a positive message, providing the tools to achieve success and setting an example himself.

“I was excited when I read about Ed’s work on climate change in a Santa Fe newspaper,” says structural engineer Vince Martinez, “so I went to work for him as a volunteer.”

A recent graduate at the time, Martinez is now Architecture 2030’s director of research and is coordinating the Seattle project. “I’m inspired by Ed every day, by his vision and his passion,” he says.

Metropolis editor Szenasy concurs. “It was Ed’s relentless yet soft-spoken advocacy for change that was responsible for the (American Institute of Architects) adopting his 2030 Challenge as its own,” she says. “His thorough commitment to positive change has inspired me from the moment I met him.”

Going global

Mazria is now busy with a companion project, the 2030 Palette, a set of comprehensive guiding principles, strategies and examples for creating healthy built environments that are tailored to specific environmental, social, economic and cultural conditions.

To be available online free of charge in about a year, the program will be translated into multiple languages so that proven methods of sustainable planning and building can be adopted anywhere in the world.

“The 2030 Palette offers design strategies to transform the world,” says Mazria. “It’s the next step in expanding the scope of the 2030 Challenge. We’re trying to get a global movement happening as quickly as possible, using the broad reach of the Internet and computer technology to reach people everywhere.”