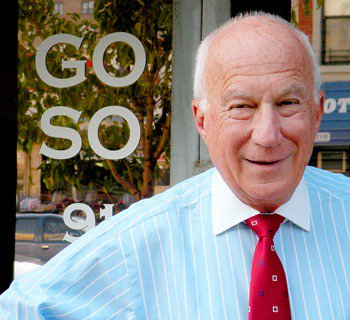

When marketing executive Mark Goldsmith volunteered to be “Principal for a Day” at a New York-area school, he asked for the program’s toughest assignment. They sent him to Rikers Island prison for a day, and that experience led Goldsmith to an encore career: helping young men plan for life after prison.

In 2003, he launched Getting Out and Staying Out to offer inmates coaching, life-skill instruction, educational guidance and job-achievement support. Participants sign contracts the day they enter the program, agreeing to attend school and be coached toward a different life upon their release. The coaches, many of them former corporate executives, help prisoners to understand what it will take to achieve success once they are released. On their first day out, they receive clothing, metro cards, an electric alarm clock, an ID card and a brand new resume. They have what they need to be interviewed for a job. The recidivism rate for Rikers Island is 66 percent, but fewer than 10 percent of Getting Out and Staying Out participants have returned on new charges since the program began.

Mark Goldsmith wanted a challenge. At 65, the cosmetics industry executive signed up for the annual Principal for a Day program in New York City. He was expecting a tough day at a tough school, but he hadn’t exactly prepared himself for Horizon Academy, a high school for 18- to 24-year-old inmates on Rikers Island.

Rikers sits on an island half the size of Central Park, surrounded by a large fence topped with coiled barbed wire. A single bridge guarded by a security checkpoint is the only way in or out. New York City’s largest corrections facility, the nine buildings on Riker’s Island house 14,000 women and men every night.

That day in 2002, Goldsmith showed up in a suit and tie, thinking he’d spend a few hours at the Academy, then go back to work. But something unlikely happened…real conversations ensued. “I don’t know why they’re listening to a white guy in a suit,” a corrections officer told Goldsmith at the end of a very long day, “but they are.”

Goldsmith was listening, too. “Nobody talks to this population,” he says. “When they’re outside, they walk around the city with their jeans hanging down, their earphones on, and nobody talks to them. All of these young men live this isolated life. They have nothing, they’re going nowhere. Then when they’re in Rikers, it’s a daily routine that never changes, they shuffle in a single line to go to meals, they shuffle back.”

Goldsmith went to Rikers again the next year. The year after that, he decided to do more than visit. He retired from his corporate job and launched a nonprofit, Getting Out and Staying Out, to help the students at Horizon Academy plan for the future.

Many prisons work with inmates a month before they’re released to get them ready for life outside. Goldsmith decided the only way to really help these young inmates was to work with them from the day they walk in to put together a plan for the day they walk out.

While in prison, the students take classes at Horizon Academy, supplemented by coaching and life skills instruction. Once released, Goldsmith urges program participants to make its storefront office in East Harlem their first stop. There they pick up a toolkit with essentials for living in the city: an electric alarm clock; identification card; subway, bus and city maps; a Metro card to pay for public transportation; a diary to keep track of appointments; condoms; and a brand-new resume. Staff members and volunteers then help them find jobs, get a GED, enroll in vocational training programs, and, if necessary, enter substance abuse treatment programs.

Getting Out and Staying Out takes on approximately 200 new Horizon students each year. Of the current 800 participants, 400 are either at Rikers or upstate; 275 work, go to school or both; and 125 still come to the office for services. Some are with the program as long as three years. Funding comes from the city, private foundations and individuals.

The program has had a stunning impact on recidivism rates. Less than 10 percent of the 400 released inmates have been arrested again since the program started in 2004. During that same period, the Rikers re-arrest rate was a dismaying two out of three.

Getting Out and Staying Out follows a business model, Goldsmith explains. “We let the guys know that we’re willing to invest in them if they’re willing to invest in themselves,” he says. To participate in the program, they submit a resume and a short essay. They also sign a contract stating that they’ll attend classes, complete their assignments and take responsibility for their actions. Goldsmith pushes them to get their general equivalency diploma as a necessary first step.

Martique, 20, soon to be released from Rikers, says he’s in jail because he had too much free time on his hands outside. “Now, my days on the street are over. I decided I wanted to be a nurse and when I get out, they’ll send me for training.” He smiles. “I’m trying to be successful and this is my chance.”

“You can’t keep living creatures in captivity and then simply throw them out in the world and expect them to survive,” says Juan Frias, assistant principal for operations at Horizon Academy. “Getting Out and Staying Out clears a path for survival.”

Goldsmith has a wide range of contacts and invites a varied group of current and retired executives to volunteer their time and share their knowledge with the students. “Many programs send less experienced people to work with inmates,” he explains. “Ours has seasoned and successful people who spend time inside with the guys.” These coaches, as he calls them, speak frankly about everything, from what makes a business tick to the legal rights of inmates to how to keep from being sent back to jail.

Richard Block, 68, is the retired CEO of a 2,000-employee entertainment-packaging company and current Getting Out and Staying Out coach. He spends two days a week at Rikers and at least an hour and a half each day at the East Harlem office. “This experience has introduced me to a hidden world and opened up for me a side of myself I had never let surface,” says Block. “It thrills me to be able to spend time that’s about something more than making money or impressing other people. Working with the guys is an amazing experience.”

All the way around, it seems.

Three months after his release from Rikers, Jeremy, 20, had an interview for a job in the duplicating department of a major law firm. He and Goldsmith practiced for three hours to get him ready. Jeremy aced the interview and got the job. “If you’re determined, they work really hard to make sure you succeed,” Jeremy says.

Goldsmith feels a connection to the young men at Rikers. “I see myself in them when I was their age,” Goldsmith says. “All I wanted to do was play ball and socialize. I was not a driven student.” He graduated near the bottom of his high-school class and joined the Navy after a couple of lackluster years in college. Marriage, more education, and a lot of hard work eventually propelled Goldsmith to success in his career.

“Now,” he says, “I feel a certain responsibility to young people. Our generation was fortunate enough to grow up with stable families, decent schools and people who counseled us. We now have a population of 18- to 24-year-old guys in every major city in this country who are unemployed, uneducated and going nowhere. Very few of them have men in their lives who aren’t either in jail or on drugs.

“If we don’t train these guys and instruct them by example, what will happen to them? It’s time to pass on what we learned. At this time of life, giving back is what it’s all about.”

Watch a video of New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg honoring Mark Goldsmith.