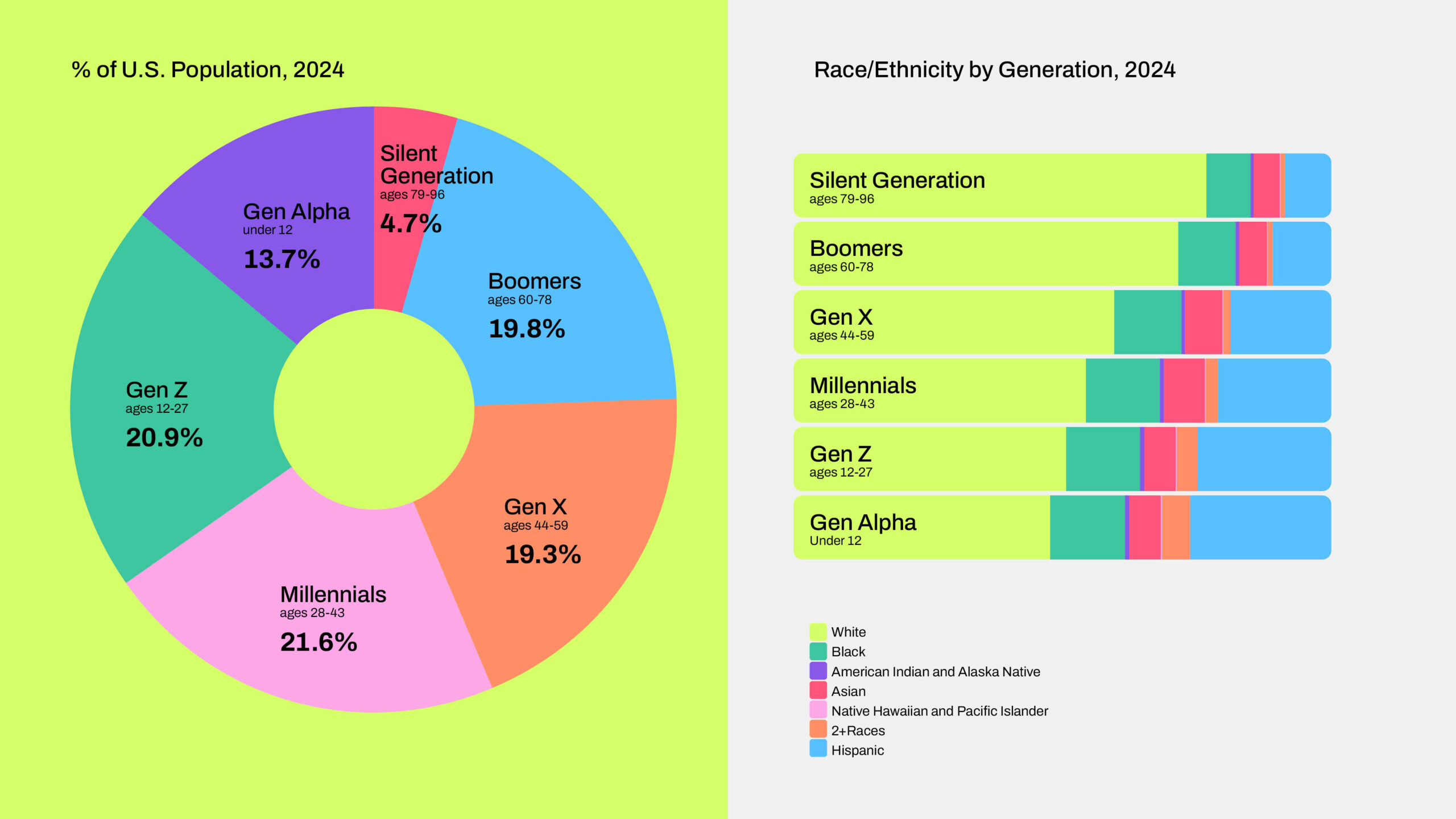

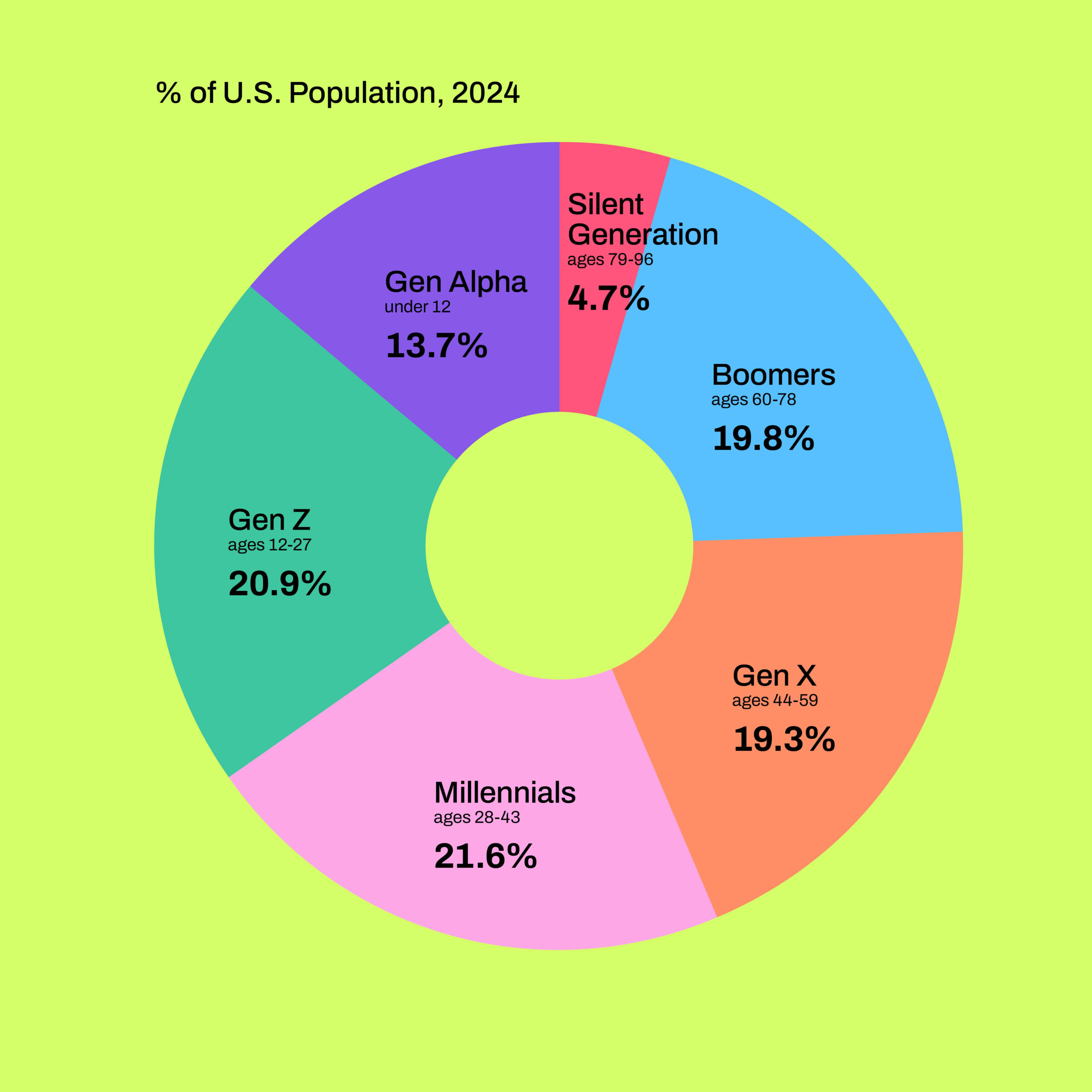

America today is one of the most age-diverse societies in history. Sadly, it is also one of the most age segregated, with older and younger people’s paths rarely crossing outside of families.

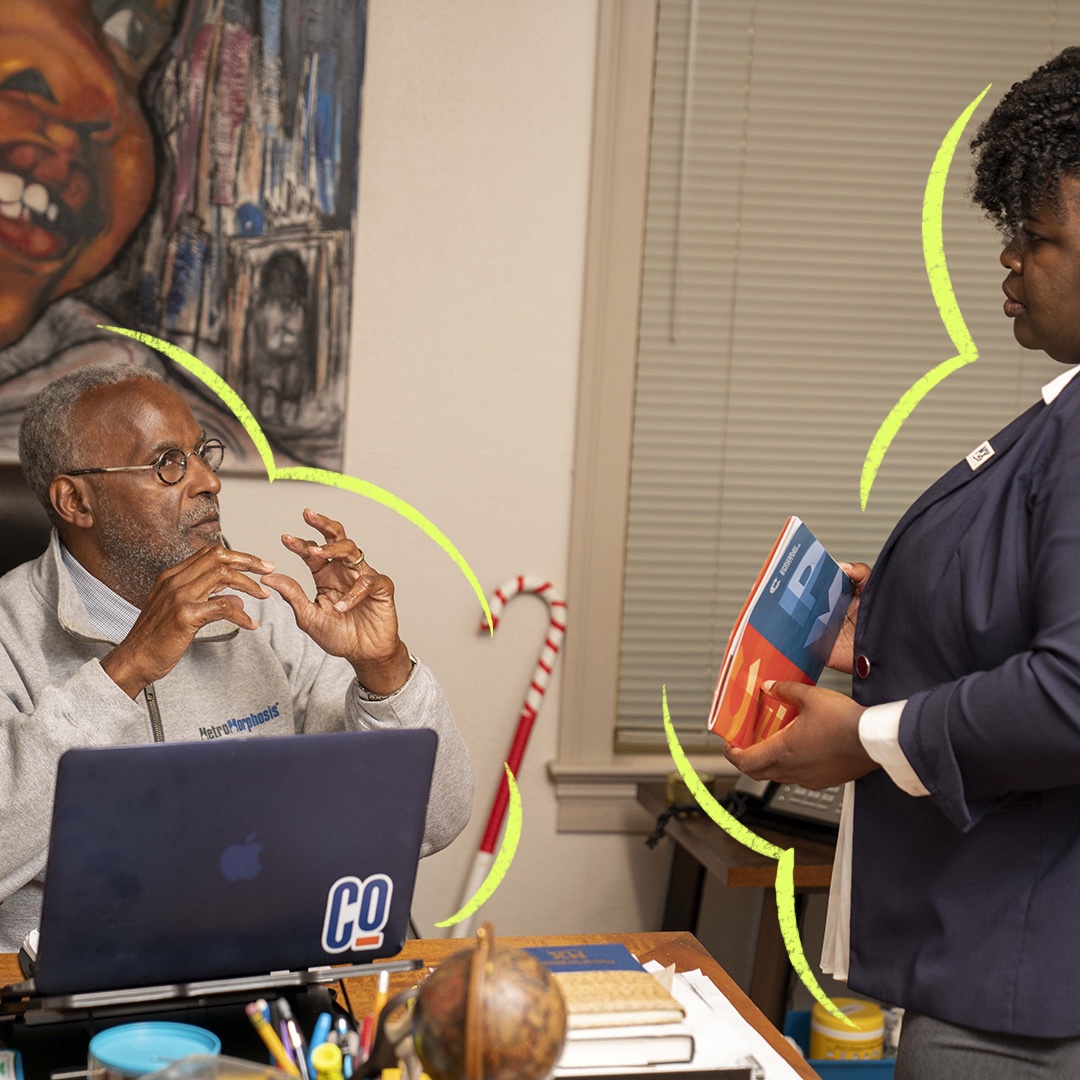

The combination of age diversity and age segregation contributes to generational conflict, ageism and misunderstanding, and the epidemic of social isolation and loneliness. It also constitutes a missed opportunity to make the most of our age diversity, to bring older and younger people together to solve the problems that no generation can solve alone.

In March of 2022, CoGenerate (formerly Encore.org) commissioned NORC at the University of Chicago to find out what a nationally representative group of Americans think about cogeneration — a strategy to bring older and younger people together to solve problems and bridge divides. We wanted to know if older and younger people want to work together to help others and improve the world around them. Turns out they do.

The research findings were clear: 81% of survey respondents aged 18-94 say they want to work with different generations to improve the world. Nearly all agree (more than half “strongly”) that we would be less divided as a society if older and younger generations worked together to improve their communities.

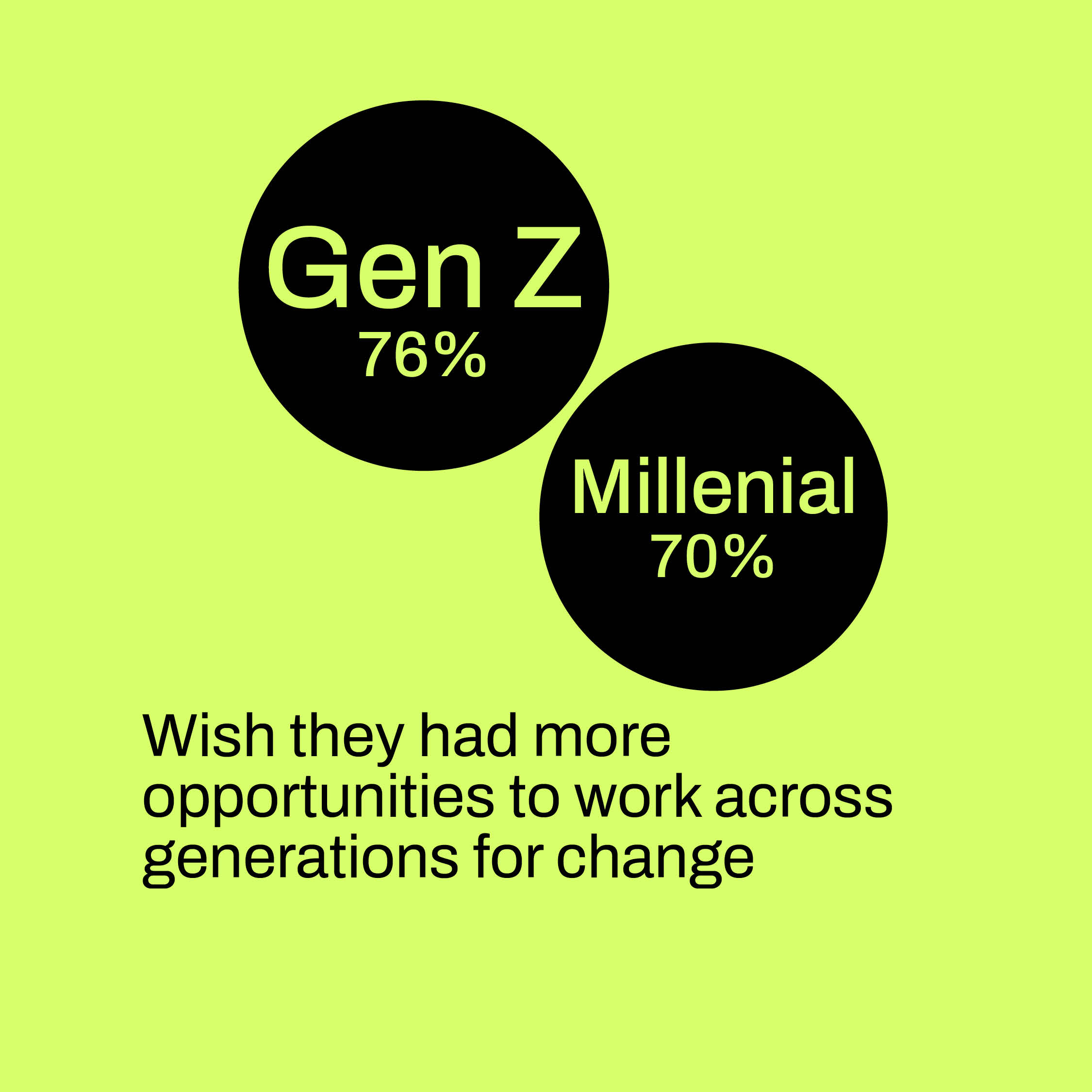

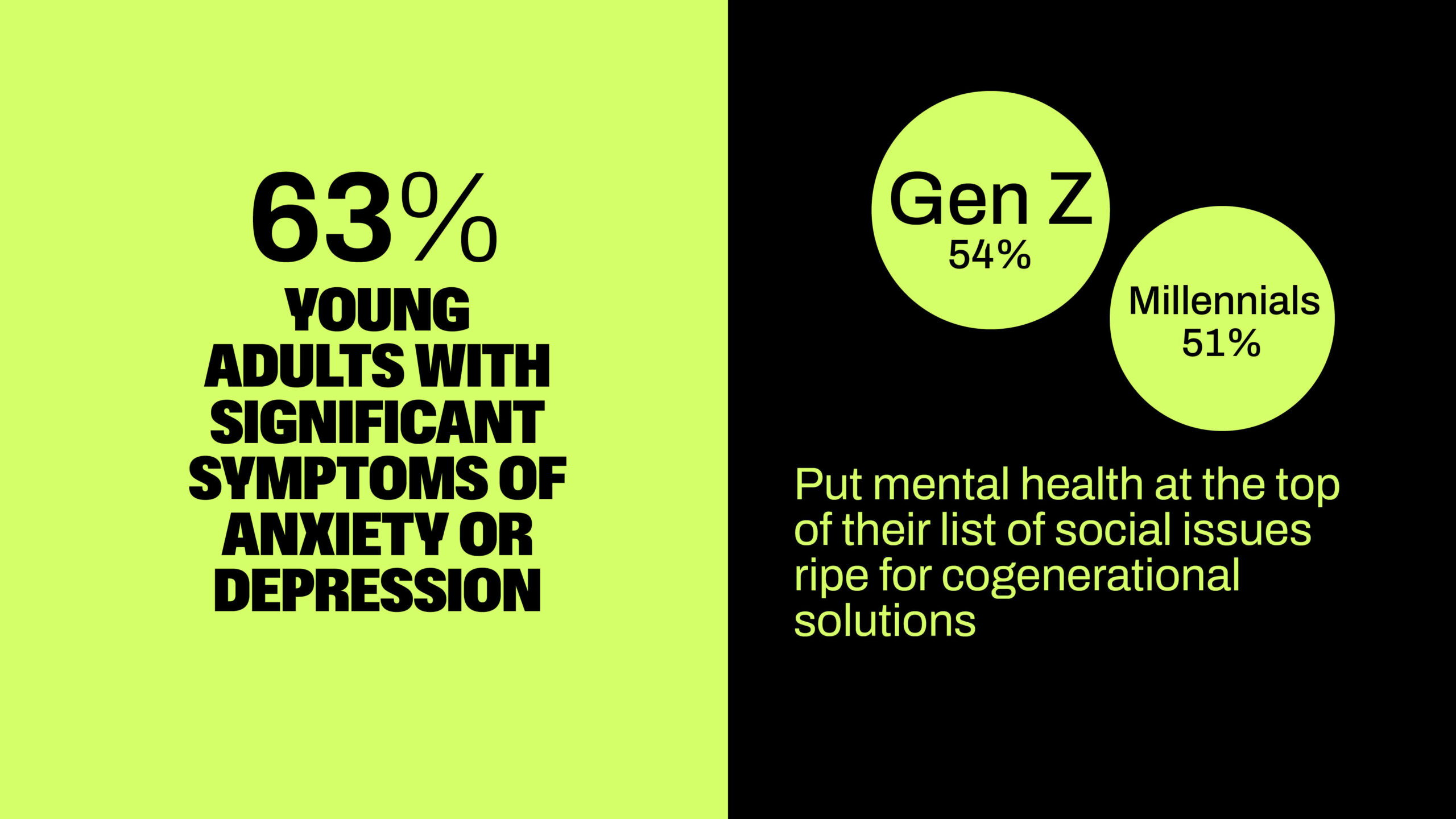

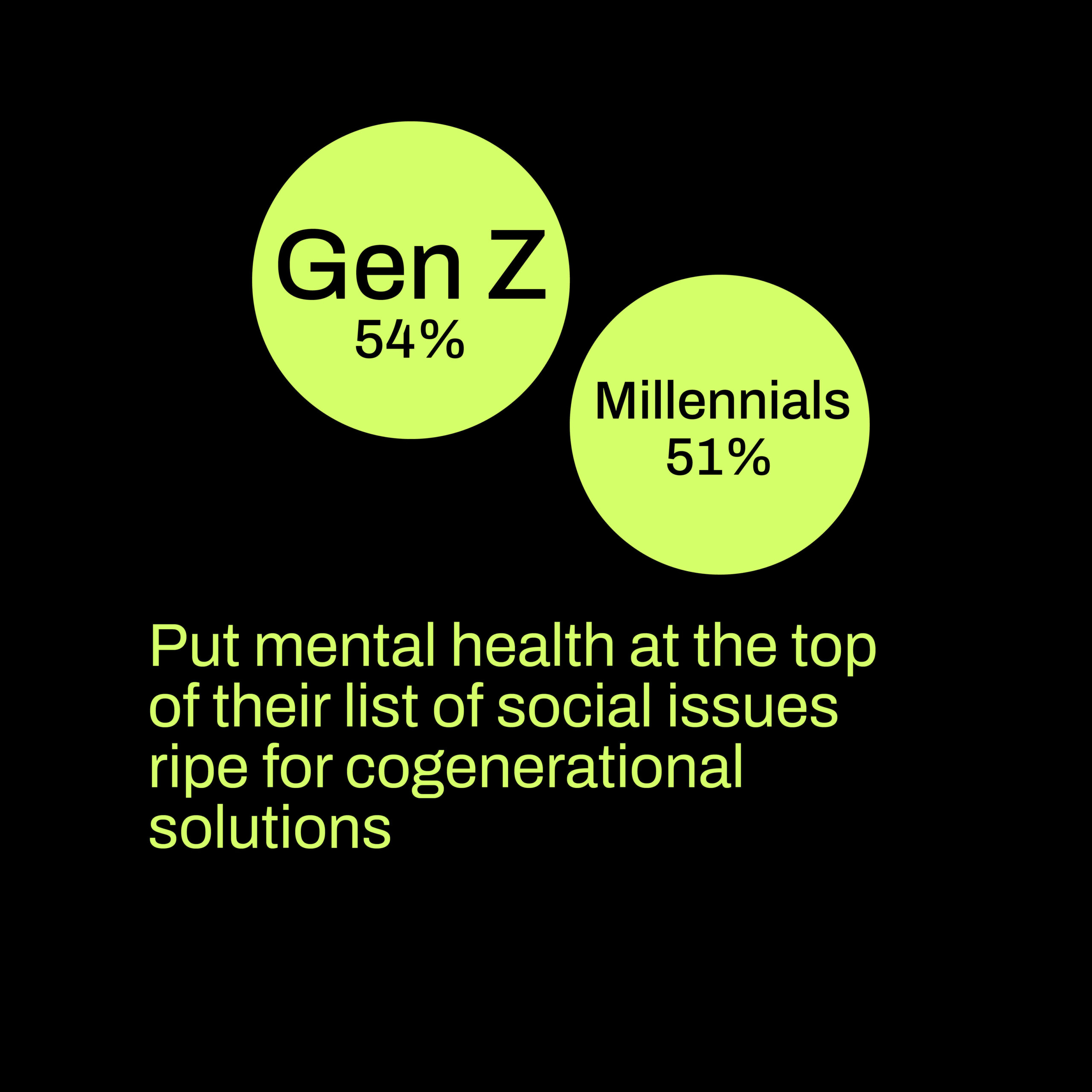

Perhaps most striking, the generation with the strongest interest in cogeneration is Gen Z. Survey results show that 76% of Gen Z and 70% of Millennial respondents say they wish they had more opportunities to work across generations for change.

We wanted to dive deeper to better understand what’s driving this interest among Gen Z and Millennials – particularly young leaders who have experience working across generations. What exactly do younger leaders want from older leaders, allies and colleagues? And how do they believe intergenerational collaboration can be improved?

With support from AARP, and additional funding from The Eisner Foundation, we set out to find answers.