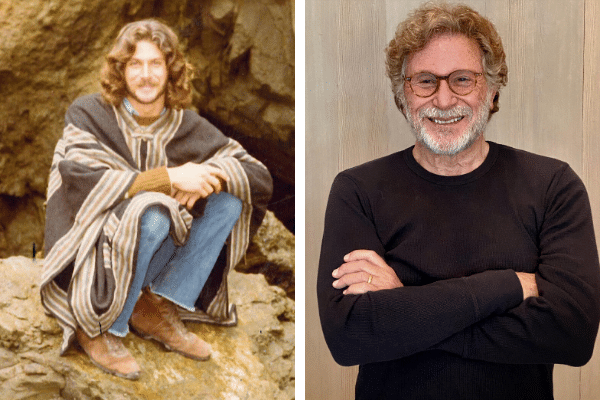

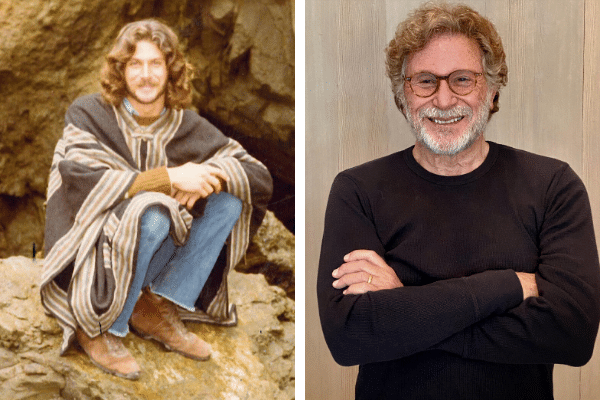

Ken Dychtwald has been interested in the power of human potential since his twenties when he was a self-described “hippie, yoga-loving guy with long hair and an earring” leading workshops at Esalen and living out of a van in Big Sur.

In the nearly 50 intervening years, he has, among other things, written 17 books, created a think tank called Age Wave, and advised half the Fortune 500 on marketing to an increasingly older population. He has given presentations to more than 2 million people and his innovative ideas are continually covered worldwide.

When I became obsessed with the encore stage of life, Dychtwald was one of my first mentors. He has been a leader in the field of positive and purposeful aging longer than just about anyone else. He has an encyclopedic knowledge of trends related to the aging of America. And he is generous with his knowledge.

His newest book, What Retirees Want: A Holistic View of Life’s Third Age, written with Robert Morison, guides readers on a range of topics Dychtwald has studied for decades — including eldercare, healthy aging, intergenerational connection, family, gray divorce, encore careers, housing, health, purpose, giving, even death.

His newest book, What Retirees Want: A Holistic View of Life’s Third Age, written with Robert Morison, guides readers on a range of topics Dychtwald has studied for decades — including eldercare, healthy aging, intergenerational connection, family, gray divorce, encore careers, housing, health, purpose, giving, even death.

The book ends on a powerful question: Will boomers use their experience and assets to help shape a future for those who follow? Or will they act only to promote their own interests?

I caught up with Dychtwald for a fascinating chat via Zoom. Here are some highlights from our conversation.

You got interested in the world of aging when you were a young man. How and why?

I was born in 1950 and after seeing Sputnik in the sky as a boy, I thought I’d become a physicist or an electrical engineer. In college, I took a class called The Psychology of Human Potential. It was taught by the “cool professor” — every campus had one! He came to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania from California with fresh ideas about how we can tap into our own natural potential to create a better mind and body.

I fell in love with these ideas and to the chagrin of my parents, dropped out of college and moved out to California where I spent six months taking workshops at Esalen [the famed personal development center], which became my new home. I’d never been west of Pennsylvania, never been in therapy, and I signed up for back-to-back workshops Friday to Sunday, Sunday to Friday for six months.

I became captivated by the mind-body relationship and started writing what became my first book, BodyMind, while completing my doctorate in psychology. I imagined this would be my forever life. Then a friend, Jean Houston, invited me to Berkeley to help her friend, Gay Luce, who was working on a curriculum on human potential.

I joined Gay and a group of us made up the phrase “holistic health” and started the Holistic Health Council. Long before Bikrim yoga classes, mindfulness training and the Ornish diet, our first project was a year-long curriculum to improve well-being, social engagement and creativity. Then Gay’s mom got sick, and Gay taught her biofeedback and tai chi – and she got better! So Gay got the idea: “Let’s do these kinds of things with old people. Let’s see if they could imagine reinventing themselves.”

I joined Gay and a group of us made up the phrase “holistic health” and started the Holistic Health Council. Long before Bikrim yoga classes, mindfulness training and the Ornish diet, our first project was a year-long curriculum to improve well-being, social engagement and creativity. Then Gay’s mom got sick, and Gay taught her biofeedback and tai chi – and she got better! So Gay got the idea: “Let’s do these kinds of things with old people. Let’s see if they could imagine reinventing themselves.”

I thought, “I’m not so sure about this,” but I told Gay that I’d do it for a couple of months. However, as the initial months unfolded, I became really fascinated by the older people. I just loved their vantage point. What is it to see life from an 80-year-old perspective? Our project became both successful and famous and before we knew it we were setting up similar projects all around the world.

I think of you as a futurist as much as an expert on the longevity revolution. Many of your predictions around aging are now upon us. Share a few that feel significant.

Back in the 1980s, I felt strongly that maturity is not just a stage of life, but that different cohorts migrate through it differently. The belief was that when you get old you become like your grandparents. I tried to lean into the idea of imagining a future of older people, but a different kind of older people than we’d ever seen before – more youthful, more curious, more open to trying new things. By the time my eighth book, Age Wave, came out in 1989, our company of the same name had a long list of government and corporate clients who were trying to make sense of changing demographics.

Television networks and publishing giants were in an absolute state of rapture with selling to young people between 15-25. I tried to alert media companies to the idea that huge numbers of 60-, 70-, and 80-year-olds will not only be citizens but also consumers.

I was also concerned about the boomer generation living for today. Living in the now is a cool pseudo-Zen way to not be so anxious, but as a financial strategy, it’s catastrophic. So how do we activate the world of financial services about the need to save and prepare financially for life’s later years?

Then, around 15 years ago, people were increasingly asking the questions, “How do you live long?” And “How much money will you need?” But what struck me was, what for? What’s the purpose of being 70 or 90 years old? What’s the obligation and purpose of being an elder in a world where there had been very few elders? I felt we were traveling blind and it troubled me that it wasn’t being discussed.

I’ve long been concerned that our healthcare system is not aligned for an aging society. I’ve written five books on that and have tried to shake up the AMA, AARP and other powers that be, but we still haven’t gotten very far. Our healthspans are still a long way away from matching our lifespans. Shame on me for not causing more change to happen.

You celebrated your 70th birthday in March. What’s surprising to you about what it feels like to be this age?

A number of things. The emotional depth of loss and fear. I didn’t expect how deep the feeling of sorrow is for so many people who are struggling with the loss of loved ones and their own old age. I was a little too glib as a young man. My mom died a few years ago in my arms. A mom dies. Everyone goes through the death of their parents. But I had not anticipated the depth of that loss.

Also, as I have learned more about brain health, I’m surprised to see how much I worry about losing my mind with Alzheimer’s.

I’m surprised by the absence of role models. It’s a good thing to have role models. What version of 70, 80, 90 do I want to be? I don’t see many older men who I aspire to be like – quite the opposite. I see a lot of older men – particularly in the political arena – acting like jerks.

On the other hand, the amount of personal power I feel is surprising to me. While I definitely am aware of having declined physically compared to when I was young, spiritually, emotionally and intellectually, I’m a whole different animal. More powerful, knowledgeable. And I even sense moments of a little wisdom budding here and there.

The desire to keep improving myself. In this stage of life, I’m trying to temper my anti-authoritarian rebelliousness with an attempt to be a kinder soul.

Renewed purpose. I thought I’d mostly take the year off, but between this new book, Covid, Greta Thunberg, Black Lives Matter, and elders not living up to their potential, I feel more stirred and involved than ever before! I’m starting my own new chapter in my own third age! It’s energizing.

The pandemic and our reckoning with systemic racism are causing and revealing enormous disparities in income, lifespan and access to medical care. How do these issues relate to the trends you study?

A Brookings Institute analysis shows a 12-year discrepancy in life expectancy between the top decile and the bottom decile of earners. This didn’t just start with Gorge Floyd and Covid. It’s been going on for a long time, but no one was talking about it.

Another thing that few folks are talking about is the racial make-up and character of old versus young generations. The 75-and-over population in the U.S. is 80% white. Boomers are 75% white. Gen Zers are majority people of color. There is a lot of racism in the older demographic, and older, white people have a great deal of voting and economic power. When they think of “the community,” they’re inclined to think of their own family, their own kids and grandchildren. Unfortunately, they don’t usually think of people unlike them.

We need a Declaration of Interdependence. As we grow older, we need to realize that we need younger people and they need us. And we have to connect with people who don’t look or pray or live like us.

If the world ever needed grownups, manifesting the best qualities of elderhood – kindness, empathy, generosity, emotional intelligence, purpose, legacy – it’s now.

One last question: Why have you chosen to put your energy into fighting against Alzheimer’s?

One of the most important dimensions of my work is that people in power – presidents, world leaders and corporate heads – have frequently asked me to look into my crystal ball and tell them about the new opportunities that will surface due to the age wave, and also the serious problems that await us. From where I sit, the biggest challenges of global aging have to do with the fact that we have failed to match healthspan and brainspan to lifespan.

Alzheimer’s is a disease that prays on the aging brain and will affect one in three people over the age of 85. Currently, there is no treatment, no cure, and it is not a quick death. The disease slowly decimates people, exhausts their loved ones, and uses up the family’s financial resources. If we could do away with it, we would have the dream of history — long lives with time for purpose, and economic benefits, too, because people could be productive longer. If we don’t wipe it out, it could be the social, spiritual and financial sinkhole of the 21st century.

His newest book,

His newest book,  I joined Gay and a group of us made up the phrase “holistic health” and started the Holistic Health Council. Long before Bikrim yoga classes, mindfulness training and the Ornish diet, our first project was a year-long curriculum to improve well-being, social engagement and creativity. Then Gay’s mom got sick, and Gay taught her biofeedback and tai chi – and she got better! So Gay got the idea: “Let’s do these kinds of things with old people. Let’s see if they could imagine reinventing themselves.”

I joined Gay and a group of us made up the phrase “holistic health” and started the Holistic Health Council. Long before Bikrim yoga classes, mindfulness training and the Ornish diet, our first project was a year-long curriculum to improve well-being, social engagement and creativity. Then Gay’s mom got sick, and Gay taught her biofeedback and tai chi – and she got better! So Gay got the idea: “Let’s do these kinds of things with old people. Let’s see if they could imagine reinventing themselves.”