We are living in the most age-diverse society in human history.

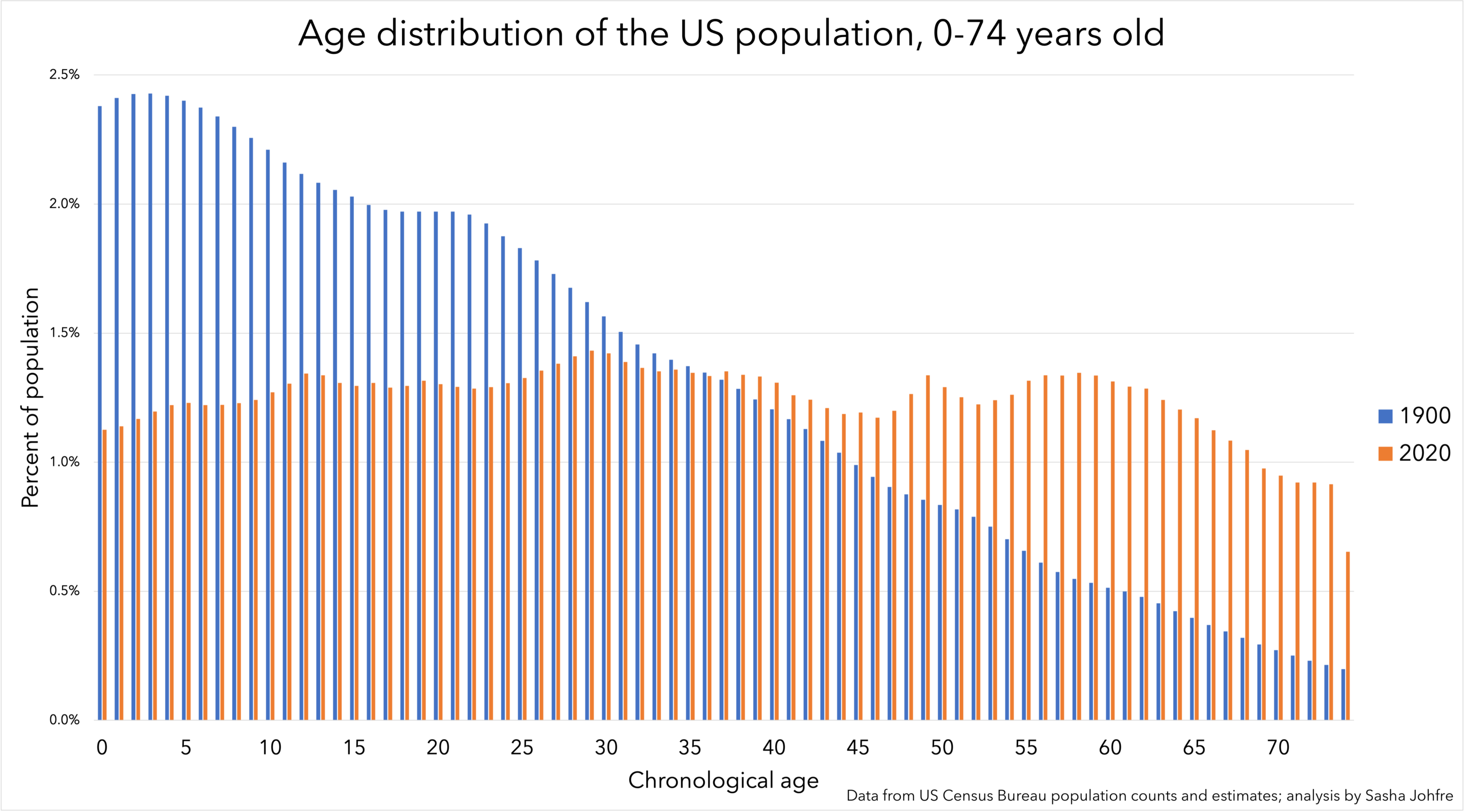

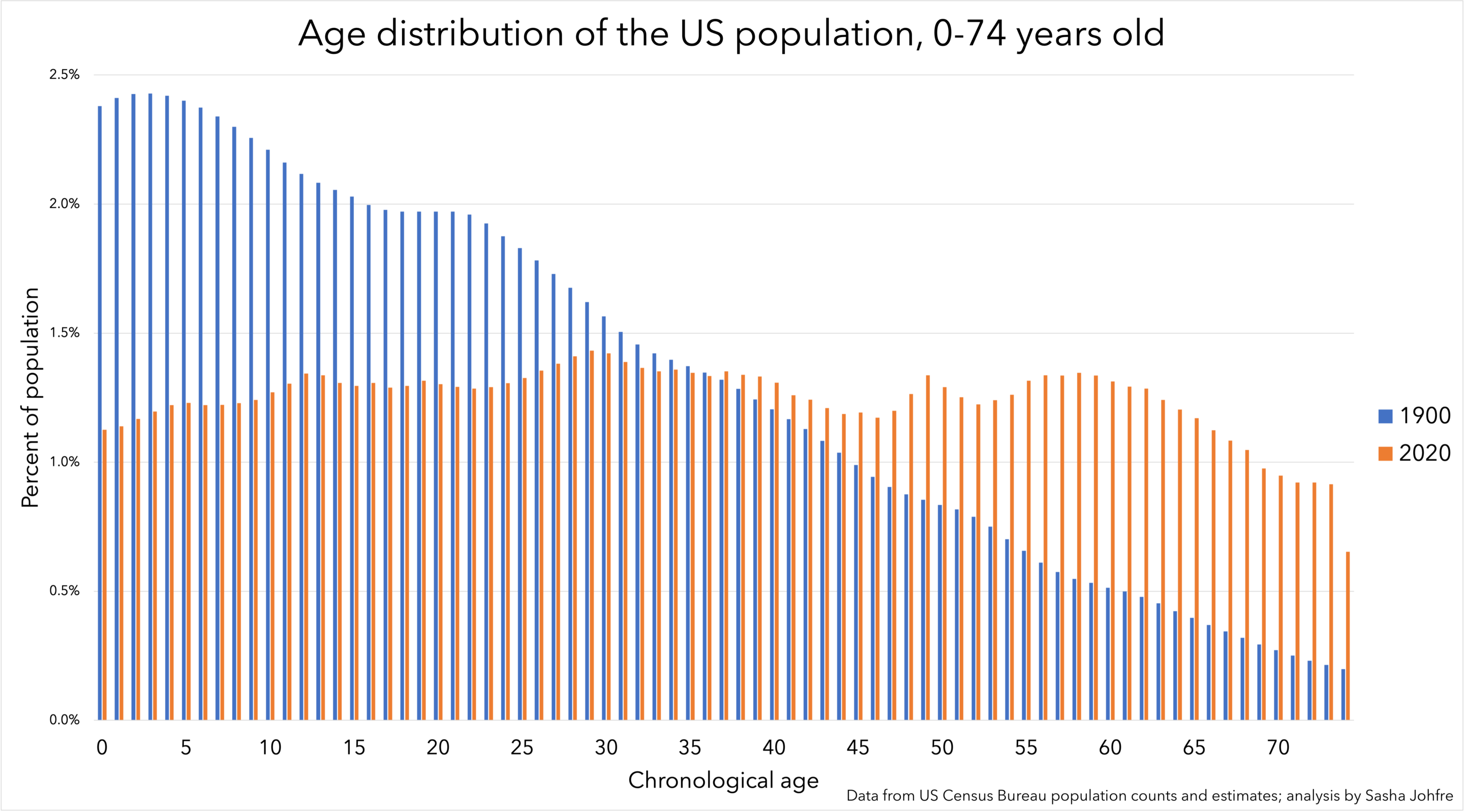

At the turn of the last century, almost half (44 percent) of the United States population was under 20 years old, and only about one in 20 (6 percent) was over age 60. The age distribution of the population in 1900 was shaped like a triangle — there were many more younger than older people, and every chronological age had fewer people than the one before it.

Today, immense changes in technology, sanitation and healthcare mean that more than half of children born today will live to be 100 years old. The population distribution is now a rectangle, with almost equal numbers of people of every age from birth to 70 and beyond. One in four people (25 percent) is under 20 years old, and similarly, about one in four people (23 percent) is over 60.

This era of age diversity offers us an unprecedented opportunity to foster relationships between people of very different ages at a scale never seen before.

Research shows that mixed-age relationships can be immensely valuable to groups and people both young and old, but that there are also intense barriers to achieving age diversity. Social forces such as age-based segregation and discrimination make it hard for people to meet, engage with and derive value from an interaction with somebody much younger or older than they are.

To help understand these obstacles, in my research with the Stanford Center on Longevity, I looked to the cultural meaning of age itself. People of different chronological ages tend to see one another as fundamentally different, which raises barriers to age integration. The family roles we take on, the jobs we have access to, our status in the workplace, the clothes we choose to wear, the activities we do, our legal rights like voting and obtaining government benefits, and our social networks all depend on how old or young we are. Sociologists sometimes call this the “age ordering” or “age structuring” of society.

This era of age diversity offers us an unprecedented opportunity to foster relationships between people of very different ages at a scale never seen before.

Despite being a force for isolation and inequality, the cultural meaning of age is also part of what can make intergenerational connection valuable in the first place. Like the known benefits of race, gender and cultural diversity, bringing people together across generational divides can introduce new ideas and encourage new levels of empathy in interpersonal relationships and groups. The very fact that we see young and old people as different is part of why it can mean so much to bring them together.

But we don’t need to get rid of age structuring to build a more connected world. We just need to change the way it operates.

For example, I have argued that believing the date on your birth certificate fundamentally explains why you look and act the way you do — a concept I call “chronological essentialism” — is a type of ageism.

There is nothing special about being alive for 6574 days rather than 6573, yet that cutoff — a person’s 18th birthday — is used as a marker of fundamental changes in maturity that imply vastly different civil rights for those on one side of it or the other.

Many social policies, as well as many of our everyday conversations about people’s ages, rest on the belief that chronological age is the most meaningful metric of messy developmental paths related to responsibility, health and intentionality. Any deviations from what is expected based on a person’s chronological age, including “looking young for your age” or “having an old soul,” are comment-worthy because they’re seen as deviations to a person’s chronological age, rather than a meaningful part of a person’s age.

There’s a better way to understand age that fits with both research on the life course and the way we talk about age as “more than a number.” We can conceptualize age itself through multiple dimensions.

Rather than focusing on chronology and deviations from it, age is best understood as a multi-faceted descriptor of a person that consists of their appearance, mobility, workplace status, family roles and hobbies, plus the year they were born. People can be young and old across many of these types of age, and we should talk about them as such without prioritizing chronology above the rest.

Understanding age through multiple dimensions can help us make sense of the way we respond to people of different ages. As an example, in the 2020 election, President Joe Biden was often ridiculed for being old, whereas President Donald Trump, only three years his junior, was not. Trump espoused his own youthful sexuality and health, while liberals across America likened the then-74-year-old to a toddler.

President Biden’s successful election suggests that, in the context of a world leader, Americans may value some of the positive things we associate with oldness (wisdom, experience, patience) more than positive things we associate with youthfulness (energy, spontaneity, playfulness). These two men (almost) share a chronological age, yet differ across many other types of age.

Our work to prioritize age diversity should encompass not just diversity of chronological ages, but also diversity of multiple types of age. Workplace teams should have people who are in their 20s and their 60s, yes, but they should also have people who are grandparents and people who are childless, as well as people who know a lot about the civil rights movement along with those who participate in the movement for Black lives.

By understanding age diversity in ways beyond just chronology, we can begin to better appreciate what aspects of diversity matter most to us and why. The logic of chronological essentialism limits us to conceptualizing age as a number, but there is so much more of value in the cultural meaning of a person’s age that we can and should harness for social good.

Sasha Johfre is a PhD candidate in sociology at Stanford and an Encore Public Voices Fellow. Don’t miss this spirited conversation she had with Encore.org founder and CEO, Marc Freedman, about what it means to live in the most age-diverse society in history.